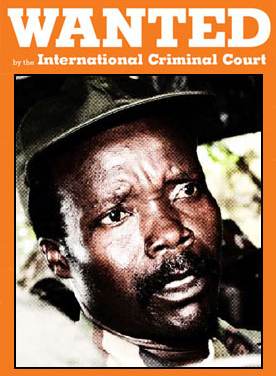

In a departure from my blog on leadership topics and leadership principles, I am posting an excerpt from my dissertation written a number of years ago as part of my Doctoral Degree in Strategic Leadership. Included as a significant aspect of those studies, one of the topics I explored was the leadership of Joseph Kony, who has been publicized widely in this current month of March by the Invisible Children organization.

The following background material is not either an endorsement of - or a critique of - the Invisible Children position on Joseph Kony. Rather, the summary that follws below provides a background on the nature of spiritual life as viewed by Joseph Kony and the majority of the citizenry of Uganda.

JOSEPH KONY AND THE SPIRITUAL NATURE OF THE CIVIL CONFLICT IN UGANDA

The history of the Ugandan people consists of the combined histories of multiple people-groups who were eventually formed into a single Nation. Each of these people-groups has a significant history of spiritual engagement which impacts the manner in which they view and proceed through life. One of the most notable (and current) impacts is attributable to the spiritual history of the founder of the Lord’s Resistance Army (“LRA”) as well as its present practice under current LRA leader Joseph Kony.

The spiritual backdrop for this movement began with the life of its founder, Alice Lakwena.

"Alice Auma was born in 1956. After two marriages in which she proved infertile, she moved away from her hometown. She eventually converted to Catholicism but, on 25 May 1985, was purportedly possessed by a spirit, Lakwena, and went ‘insane,’ unable to either hear or speak. Her father took her to eleven different witches but none could help. According to the story, finally Lakwena guided her to Paraa National Park where she disappeared for 40 days and returned a spirit-medium, a traditional ethnic belief...it is claimed that on 6 August 1986 Lakwena ordered Alice to stop her work as a diviner and healer...and create a Holy Spirit Movement (HSM) to fight evil and end the bloodshed."[1]

Accordingly, Alice Auma, an Acholi from the North of Uganda, proceeded to rename herself Alice Lakwena and began to implement the instructions she had “received” from the demonic spirit named Lakwena. She thereafter formed an army which she named the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces later renamed the Lord’s Resistance Army. Recounting the spiritual nature of her story, we learn that,

"[Lakwena] was the Chairman and Commander in Chief of the movement; other spirits – like Wrong Element from the United States, Ching Po from Korea, Franko from Zaire, some Islamic fighting spirits, and a spirit named Nyaker from Acholi – also took possession of her. These spirits conducted the war. They also provided other-worldly ligitimation for the undertaking."[2]

It was further believed that additional so-called protective spirits provided a forward gauntlet and a rear guard to the soldiers who followed Alice into battle.[3] An important point to make is that, “in the local view, it is the spirits, and not the possessed people [who] are the active parties.”[4] Thus, in the understanding of the local Ugandan population, the civil conflict they experience does not so much have a spiritual element as, more forcefully, such conflicts are entirely about the interaction and leadership provided by such spirits. In their minds, the conflict is a spiritual conflict – period.

Even so, following a series of military defeats in 1988, and according to popular understanding, when which point the spirit Lakwena became dissatisfied with Alice Auma, this spirit entered her father, Severino Lukoya, who then assumed command of Alice Auma’s soldiers.[5] He almost immediately suffered a series of defeats and, in 1989, withdrew from the field of battle.

The insurgency of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces was promptly replaced by the LRA, led by Joseph Kony, which had initiated a military campaign against the Museveni government and which was similarly infused with spiritual overtones and spiritual guidance. While Kony’s reliance on spiritual forces is well established, the specifics are not as clear. Some reports indicate that, “Joseph Kony claimed to inherit the spiritual powers of Lakwena from his first cousin Alice.”[6] Other reports claim that there is a distinction and that “Kony introduced completely new and previously unknown spirits. Only their character, duties, and tasks exhibit a certain resemblance to, and continuity with, the spirits of the other movements.”[7]

Regardless, Kony and his LRA have exhibited consistent belief in - and reliance on - direction and empowerment from the unseen world of the spirits. “[The LRA] do not believe that they kill people, but that the gods (spirits) are the ones who use them, believers in the spirits, to punish those who disobey the commands of the gods.”[8] Therefore, “despite clear biblical injunctions against murder, mutilation and torture, Kony believes himself to be fulfilling a spiritual calling.”[9] In fact, first-hand reports from the region confirm the hypocrisy Kony’s so-called commitment to impose the Ten Commandments. Sam Farmer met with Kony at a remote and undisclosed location in Southern Sudan. He reports that, “The LRA combined the fanaticism of a cult with ruthless military efficiency, and while its apparent aim was to impose the Ten Commandments on Uganda, its means could scarcely have been more evil.”[10] From his interview, Farmer discovered Kony’s belief that,

"He was guided by spirits, he said. [Quoting Kony] “They speak to me. They load through me. They will tell us what is going to happen. They say ‘you, Mr. Joseph, tell your people that the enemy is planning to come and attack’. They will come like dreaming, they will tell us everything. You know, we are guerrilla. We are rebel. We don’t have medicine. But with the help of spirit they will tell to us, ‘you Mr. Joseph go and take this thing and that thing.’”[11]

Thus the continued civil strife in Northern Uganda is described by its leaders in spiritual terms and understood by the Ugandan population as a spiritual conflict. Accordingly, the Ugandan population in the conflict-riddled north operates very openly in the natural/spiritual context of one world, consisting of two realms (natural + spiritual).

Other regions of Uganda share the history and practice of defining their existence in terms of the combined reality of a spiritual-and-natural-realm context. For instance,

"The Kabaka is the title of the King of Buganda. Under the traditions of the Baganda, they are ruled by two kings: one spiritual and the other - a human-being prince. The spiritual (supernatural being) king...always exists, thus Buganda at any single time will always have a king. [The spirit being} Mujaguzo, like any other king in the world, has his own palace, officials, servants and guards assigned to his palace."[12]

The Buganda people in the south are not alone in the view of the existence of one world consisting of two realms. In the northwest corner of the country, the Lugbara people practice a form of ancestor worship which includes the belief that the spirits of departed ancestors in the spirit realm maintain contact and influence in the present earthly realm. All of life is interpreted in the context of the interplay of the spirits between the two realms.

"The Lugbara of Uganda believe that the living and the dead of the same lineage are in a permanent relationship with each other. As a result, the dead are aware of the actions of the living and care about them, whom they consider as their children. However, in some circumstances, the dead send sickness to the living, in order to remind them that they are acting custodians of the Lugbara lineages and their shrines."[13]

Further research documents the existence of numerous other belief structures which affirm the active involvement of Ugandans in the theme of natural-world and spirit-world interaction.

"An important example of this religious attitude is found in western Uganda among members of the Mbandwa religion and related belief systems throughout the region. Mbandwa mediators act on behalf of other believers, using trance or hypnosis and offering sacrifice and prayer to beseech the spirit world on behalf of the living."[14]

Yet another example is found in the Ganda belief system where,

"...Most spiritual beings are considered to be the source of misfortune, rather than good fortune--forces to be placated...Important gods in the Ganda pantheon include Kibuka and Nende, the gods of war; Mukasa, the god of children and fertility; a number of gods of the elements--rain, lightning, earthquake, and drought; gods of plague and smallpox; and a god of hunting. Sacrifices to appease these deities include food, animals, and, at times in the past, human beings."[15]

While each of the historic kingdoms and people groups may not share the exact same spiritual history, it is established historically that there is a spiritual practice inherent within the life and culture of each of these groups. “Most religions involve beliefs in ancestral and other spirits, and [the Ugandan] people offer prayers and sacrifices to symbolize respect for the dead and to maintain proper relationships among the living.”[16]

SUMMARY

The LRA insurgency in Northern Uganda has had a spiritual history dating back to the rebel group’s original founder, Alice Lakwena. In addition, the principal tribe of south and central Uganda which consists of the Buganda Kingdom, as well as each of the major people groups in Uganda, whether they are defined by one of the traditional kingdoms or, more typical of the north, by their historic people-group, has its own spiritual history.

In every case, it is not uncommon for these people-groups to continue to honor their own distinct spiritual customs, even in modern-day life. In a nation which is considered to be “two-thirds Christian,” the tendency is to simply add the traditional religious customs to the tenants of the Christian faith, thereby creating a mixture comprised of Christian faith and pagan ritualistic practices.

There is therefore solid evidence that the spiritual realities with which the people have historically engaged continue to “inform and direct” the actions of the leadership of the civil conflict in the regions that comprise modern-day Uganda. As previously illustrated, nowhere is this more apparent than in Northern Uganda through the activity of Joseph Kony and his leadership of the LRA.

[1] “Alice Auma,” Wikipedia, n.p. [cited 10 Jan. 2007].

Online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Auma.

[2] Heike Behrend, Alice Lakwena & the Holy Spirits (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 1999), 1.

[3] Behrend, Alice Lakwena, 133.

[4] Behrend, Alice Lakwena, 138.

[5] Behrend, Alice Lakwena, 175.

[6] Rory E. Anderson, Fortunate Sewankambo and Kathy Vandergrift, Pawns of Politics; Children, Conflict and Peace in Northern Uganda (Federal Way: World Vision International, 2005), n.p.

[7] Behrend, Alice Lakwena, 185.

[8] Anderson, Sewankambo, Vandergrift, Pawns of Politics, n.p.

[9] Anderson, Sewankambo, Vandergrift, Pawns of Politics, n.p.

[10] Sam Farmer, “Come Back Alive,” BBCOnline, n.p. [cited 12 Mar. 2007]. Online: http://www.comebackalive.com/phpBB2/viewtopic.php?t=18846&view=next&sid=....

[11] Sam Farmer, “Come Back Alive,” n.p.

[12] “Kabaka of Buganda,” Wikipedia, n.p. [cited 4 Dec. 2006]. Online: encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabaka_of_Buganda.

[13] “Lugbara Religion,” Overview of World Religions, n.p. [cited 10 Jan. 2007]. Online: http://philtar.ucsm.ac.uk/encyclopedia/sub/lugbara.html.

[14] “Uganda: Local Religions,” Library of Congress Country Studies, n.p. [cited Mar. 11, 2007]. Online:

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ug0055).

[15] “Uganda: Local Religions,” n.p.

[16] “Uganda: Local Religions,” n.p.